Talk:Public finance (COVID-19 monograph)

The COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. First wave: from the first cases to the end of June 2020

Monographs from the National Atlas of Spain. New content

Thematic structure > Social, economic and environmental effects > Public Finance

The COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted the need for public action to lessen the noxious effects of social and natural events that may seriously disrupt the smooth running of societies. Public action is financed by tax revenue. Scrutinising public resources requires assessing the two basic composing elements, i.e. public revenue and public expenditure.

The impact of the pandemic on revenue may be assessed by taking two aspects into account. First, the evolution of tax collection before and during the health crisis. Second, the uneven geographical patterns of said tax collection as a result of the different productive and business structure in the various Spanish regions and thus the dissimilar income levels of citizens.

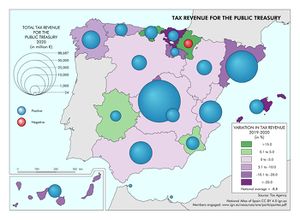

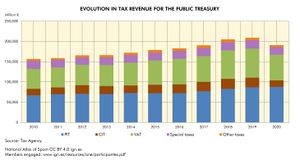

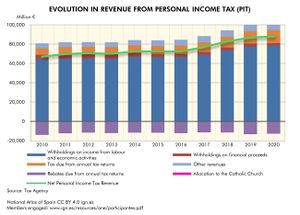

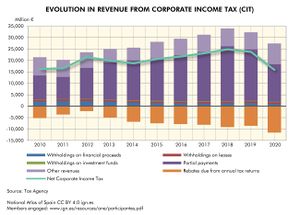

The graphs show the evolution in the tax revenue for the Public Treasury from 2010 to 2020. This revenue is bred by the three main taxes that are available to the National Administration, i.e. Value Added Tax (VAT), Personal Income Tax (PIT) and Corporate Income Tax (CIT). A more modest contribution comes from special taxes levied on alcohol, tobacco and fuel consumption.

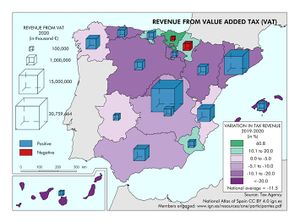

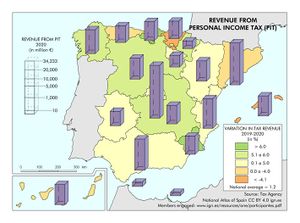

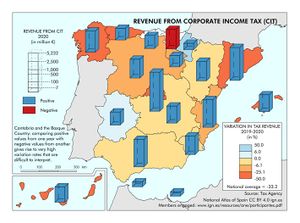

These graphs are displayed together with four maps showing the amount of taxes collected in each region in 2020 for each of the different taxes, as well as the variation in the amount of taxes collected from 2019 to 2020.

The first topic to be assessed is the overall tax revenue for the Public Treasury, considering the Personal Income Tax, the Value Added Tax, the Corporate Income Tax and the special taxes on alcohol, tobacco and fuel. The graph on the Evolution in tax revenue for the Public Treasury shows a steady increase in tax collection from 2010 to 2019 as a result of the gradual recovery in Spain from the double economic crisis back in 2008-2013. This increase in revenue speeded up from 2017 onwards when Spain finally broke free of the economic hangover left by the 2008-2013 recessions.

These graphs are displayed together with four maps showing the amount of taxes collected in each region in 2020 for each of the different taxes, as well as the variation in the amount of taxes collected from 2019 to 2020. The first topic to be assessed is the overall tax revenue for the Public Treasury, considering the Personal Income Tax, the Value Added Tax, the Corporate Income Tax and the special taxes on alcohol, tobacco and fuel. The graph on the Evolution in tax revenue for the Public Treasury shows a steady increase in tax collection from 2010 to 2019 as a result of the gradual recovery in Spain from the double economic crisis back in 2008-2013. This increase in revenue speeded up from 2017 onwards when Spain finally broke free of the economic hangover left by the 2008-2013 recessions.

In 2020, however, revenue took a remarkable hit due to the impact of the pandemic on Value Added Tax, which faithfully and immediately reveals the behaviour of the economic cycle. Personal Income Tax and Corporate Income Tax do not seem to be affected by COVID-19 according to the graphs included in this publication as the tax revenue from 2020 is levied on the income and profits from 2019, when the COVID-19 crisis had not yet began. Nor is there a heavy impact on special taxes, which depend on deeply rooted consumption habits, i.e. alcohol and tobacco. There is, however, a remarkable drop in revenue from fuel consumption due to lockdown and mobility restrictions in spring 2020.

In terms of geographical patterns, the map on the Tax revenue for the Public Treasury shows an aggregate distribution of revenue that is consistent in general with the distribution of the population and the economic activity in Spain. The Region of Madrid (Comunidad de Madrid) and Catalonia (Catalunya/Cataluña) are well ahead the other regions thanks partly to being home to the headquarters of manifold large companies. A second tier includes Andalusia (Andalucía), the Region of Valencia (Comunitat Valenciana) and Galicia. The most interesting aspect of this map, however, is the dynamics it reveals. From 2019 to 2020, the regions with a solid agri-food base, such as Navarre (Navarra), Cantabria, Extremadura and Murcia, were able to increase figures on the total revenue despite the general downward trend seen elsewhere. By contrast, tourist regions like the Balearic Islands (Illes Balears) and the Canary Islands (Canarias) registered a very severe negative impact on tax collection. This regression may also be observed in other regions with a significant industrial base, such as the Basque Country (Euskadi/País Vasco) and Catalonia (Catalunya/Cataluña), which were affected by the distortion in global value chains that arose in China and later spread to the rest of Asia, the Americas and Europe.

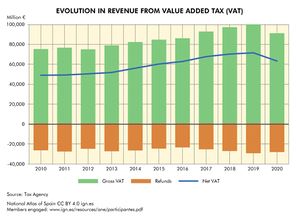

The other maps break down these aggregate figures into each of the three main tax revenues. There is a general upward trend in revenue from Value Added Tax after 2010, which becomes more evident after 2016 and then takes a significant downturn in 2020. The regional distribution of the total revenue collected clearly shows the ‘headquarters effect’ in the Region of Madrid (Comunidad de Madrid) and Catalonia (Catalunya/Cataluña) [especially Barcelona], whose many large corporations bred negative revenue variations and, therefore, paid less tax, as well as the Basque Country (Euskadi/País Vasco). Once again, the regions of Murcia, Navarre (Navarra) and Cantabria followed positive trends, highlighting their crucial economic role as suppliers of essential agri-food goods in times of crisis. Together with the Basque Country (Euskadi/País Vasco), these three regions are the only ones to show increased revenues in a regressive national context that registered an average drop of 11.5%. At the opposite end of the scale are the two island regions, i.e. the Balearic Islands (Illes Balears) and the Canary Islands (Canarias), with falls of over 20% due to tourism vanishing from sight during strict lockdown and the subsequent travel restrictions.

As data on Personal Income Tax from 2020 show earnings from 2019, they do not reveal the impact of the pandemic on economy and public revenue. Moreover, figures show an overall year-on-year growth of 1.2%, with Cantabria registering an increase over 6%, and only Asturias, Catalonia (Catalunya/Cataluña), the Basque Country (Euskadi/País Vasco), the Balearic Islands (Illes Balears) and the Canary Islands (Canarias) showing a negative evolution. Given that the bulk of this tax is levied on income from work and professional activities, the amount collected in each region depends on both its total population and the income level of citizens. Therefore, the Region of Madrid (Comunidad de Madrid) and Catalonia (Catalunya/Cataluña) stand out for breeding more revenue from Personal Income Tax than the rest of regions. The significance of population in the revenue bred by this tax explains why inter-regional differences are less acute than in the other taxes, which are more affected by the evolution of activity and company profits than by the amount of contributors. Hence, the Balearic Islands (Illes Balears), the Canary Islands (Canarias), the Basque Country (Euskadi/País Vasco), Cantabria and Galicia account for a larger share of the national Personal Income Tax revenue than they do for Value Added Tax or Corporate Income Tax.

Revenue from Corporate Income Tax has been following a downward trend since 2018 that reached a national average fall of 33.2% from 2019 to 2020. The decline in revenue was widespread throughout the whole country, and particularly remarkable in the two island regions, i.e. the Balearic Islands (Illes Balears) and the Canary Islands (Canarias). In this context, the only regions to see positive trends were Navarre (Navarra) and Extremadura, whose companies were showing signs of strength before the pandemic.

An overall assessment of these figures allows sketching some general lines of interpretation. Firstly, the high degree of specialisation in tourism in the Balearic Islands (Illes Balears) and the Canary Islands (Canarias) extended throughout their entire economic and social structures, including employment. This factor seriously limited the capacity of the public administrations to act by undermining their budgetary resources. Secondly, and conversely, diversified regional economies, such as the Region of Murcia (Región de Murcia), Navarre (Navarra), Cantabria and Extremadura, where industry and the agri-food sector account for a sizeable part of the productive structure, proved more resilient to the impacts of the pandemic. Consequently, more attention shall be paid to the productive sectors that are truly essential for the smooth running of society. Thirdly, the difficulties observed in industrial regions, such as Catalonia (Catalunya/Cataluña) and the Basque Country (Euskadi/País Vasco), and those hinged on the tertiary economy, such as the Region of Madrid (Comunidad de Madrid), were probably derived from their intense insertion and, therefore, increased exposure to global economic flows. Furthermore, for the Region of Madrid (Comunidad de Madrid) and Catalonia (Catalunya/Cataluña) [more specifically Barcelona], being the headquarters of large corporations at a time when many were returning negative results entailed significant effects on tax revenue.

Public expenditure

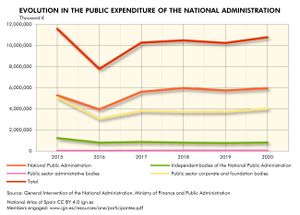

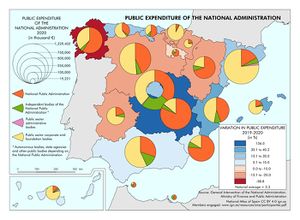

The pandemic tested the capacity of the Public Administrations (national, regional and local) to react to the effects of the crisis on the business fabric and on society in general, especially on a social level (health, education and labour market). On the one hand, the sharp drop in economic activity forced implementing and extending direct support mechanisms, such as furloughs, which mobilised large amount of resources to cushion the impact of the pandemic on employment and on the business fabric and pave the way for a rapid recovery. On the other hand, basic public services, such as health and education, required additional funding to serve the population directly affected by the disease, roll out a mass vaccination programme, and ease non-face-to-face teaching modes and smaller student/teacher ratios.

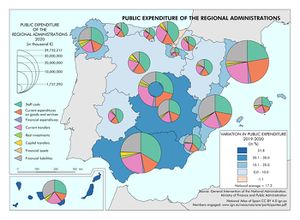

As a result, the expenditure of the National Administration and its dependent agencies and bodies registered a year-on-year increase of 5.3% in 2020, reaching high levels of expenditure that were kept throughout 2021. This increase in expenditure was most remarkable at regional level as regions are responsible for providing public services linked to the welfare state, i.e. social services, health and education. In addition, regional administrations implemented where possible smaller initiatives to directly support economic activity, including the granting of subsidies to companies in those sectors that were most affected by restrictions, such as tourism and food and beverage services. The expenditure incurred by the regions grew in 2020 by 17.2% with respect to the previous year. The increased expenditure was particularly significant in the regions with larger general financing deficit, such as the Region of Valencia (Comunitat Valenciana), the Region of Murcia (Región de Murcia) and Andalusia (Andalucía). The National Administration played a decisive role in enabling the regions to act by making credit available to them via the traditional Regional Liquidity Fund and also by creating specific funds, such as the COVID Fund, which mobilised 16 billion euro in 2020. This fund was primarily distributed according to the incidence of the pandemic and size of the population in each region, a marked departure from the criteria usually used to finance the regions within the general tax regime [NOTE: all regions in Spain are part of the general tax regime, except for the Basque Country(Euskadi/País Vasco) and Navarre (Navarra), which have a different tax collection regime].

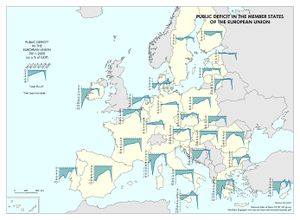

The increase in public expenditure went hand in hand with a significant reduction in tax revenues, resulting in a rise in the public deficit that was financed by issuing public debt. This was made possible by highly expansionary monetary policies from the European Central Bank, which kept negative interest rates and implemented aggressive programmes to purchase the public debt of its Member States. The decision of the European Union to suspend the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact allowed EU Member States to run ‘excessive’ public deficit avoiding any penalisations.

The combined public deficit of all Spanish public administrations (national, regional and local) was close to 12% in 2020, i.e. the highest amongst EU states, and slightly over the public deficit recorded in the depths of the great recession of 2008-2013. No other major EU economy registered such an acute rise in public deficit. France and Italy were significantly impacted, registering deficits of around 9%, whilst Germany and the Netherlands managed to limit theirs to 4%. It shall be noted, however, that Central European states have healthier public accounts due to having been less affected by the 2008-2013 financial crisis. Spain obtained therefore significant relief from monetary easing policies and financial support. However, it could equally be severely affected by a return to the constraints of the Stability and Growth Pact, and what this return to budgetary discipline should look like will be a major political issue in the European Union in the coming years.

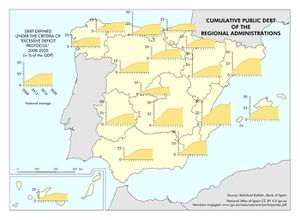

Within Spain, this rise in public deficit entailed a further increase in the cumulative debt of the regions in relation to their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This ratio had been stabilising or even slightly decreasing after the peak from 2015 and 2016 (see the map on the Cumulative public debt of the Regional Administrations). Just as there are disparities between the different EU states, also the different Spanish regions show sharp contrasts. In some, such as the Region of Madrid (Comunidad de Madrid), the Basque Country (Euskadi/ País Vasco) and Navarre (Navarra), the debt did not exceed 20% of GDP in 2020 and indebtedness with the national administration was non-existent. Others, such as the Region of Valencia (Comunitat Valenciana), are in debt to the tune of nearly 50% of their regional GDP, and four-fifths of this debt is owed to the national Public Treasury. These historical disparities in regional debt levels, which were further sharpened by the pandemic, may largely be explained by regional differences in income per capita, tax bases and the complexity of the tax revenue distribution system between the different regions in Spain.

Co-authorship of the text in Spanish: Juan Miguel Albertos Puebla and José Luis Sánchez Hernández. See the list of members engaged

You can download the complete publication The COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. First wave: from the first cases to the end of June 2020 in Libros Digitales del ANE site.