Talk:Ancient Age

Spain on maps. A geographic synopsis

Compendium of the National Atlas of Spain. New content

Thematic structure > History > Historical overview > Ancient Age

Until relatively recently, the Ancient Age was widely considered to have begun in the Orient with the advent of writing, roughly 5,000 years ago. Today, other factors are also taken into account when situating this period in the timeline of history, such as the way societies were organised, diversification with respect to production and consumption, transport systems, and lastly, the appearance of more advanced civilisations that have gone down in history or, in other words, have persisted in our collective memory.

From this new perspective, the Ancient Age on the Iberian Peninsula is thought to have begun during the Iron Age II, although the last two millennia BC appear to be more typical of the Neolithic period, which was characterised by the use of metallurgy, and therefore cannot be dated to Prehistory with total certainty. Nevertheless, it is much more complicated to define the ending of the Ancient Age. According to some scholars, it concluded with the rise of the Visigoths in the 6th century, while others contend that it was the Moorish invasion (in the Battle of Guadalete) in the year 711 (three centuries later) that marked its ending. Additionally, these theories raise the question of whether the reign of the Visogoths can be referred to as the first Spanish nation-state. If so concluded, the Middles Ages would only have been a period of re-conquest (la Reconquista). Or perhaps, this three-century-long period was merely a continuation of Roman rule (Antiquity). There is a longstanding historiographical debate about whether the origin and essence of Spain begin with Hispania, or if Spain is something much more recent, as far as the 19th century. In any case, as previously mentioned, belief in one historical theory does not preclude consideration of other differing theories.

One thing we know for certain is that at the end of the Iron Age, the Iberian Peninsula was in the throes of war for the first time. This violent reality marked the dawning of the Ancient Age on the Peninsula and the transition to the historical era. The ending of the Ancient Age is widely taken to have occurred sometime between the 5th and 8th centuries AD. These three centuries, spanning from the end of Antiquity to the beginning of the Middle Ages, have been termed The Transition to the Middle Ages. By this time, a definition of the Iberian Peninsula was taken into account as a unified territory, already medieval in nature, with its own borders and institutions. Its development paralleled the rise of the Republic of Venice, the expansion of the Franks with its epicentre in Paris, the shift from Latin to Greek in the Eastern Roman Empire, and the appearance and spread of Islam from Anatolia to Gibraltar, ending at the “mare nostrum”.

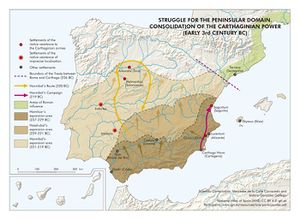

In the initial years of the Ancient Age on the Peninsula, Carthage, an ancient Phoenician colony of Tyre, near modern day Tunis, had become a great maritime island empire in the Western Mediterranean. After Tyre had been conquered by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in the 6th century BC, Carthage´s influence began to grow, eventually dominating the region. Over time, on the Peninsular coasts and Balearic Islands, the Carthaginians replaced the Phoenicians who had periodically disembarked on the Iberian Peninsula to work in factories and storehouses since the 9th and 8th centuries BC. Greek explorers from Phocaea and the enclave of Massilia (Marseille) also arrived, and according to older historical sources, established a number of colonies; however, further studies of some of the remains in these areas suggest they belonged to Greeks who were only there engaging in trade with the earlier Phoenician enclaves.

Between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC, the Carthaginian Empire had already consolidated its power. By the 3rd century, it was embroiled in a series of conflicts with the emerging, powerful Roman Empire over the control of Sicily. In the first Punic War, the Carthaginian settlements of Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia were lost to the Romans. The Carthaginians, led by the Barca clan, were in search of a strategic base with logistical advantages on the Iberian Peninsula. In 227 BC, Carthago Nova (Cartagena) was founded.

Subsequently, Carthaginian General Hamilcar Barca took the indigenous peninsular tribes and mining sites under his control, either by force or by means of agreements. His successors, Hasdrubal (his son-in-law) and later, his sons, Hannibal and Hasdrubal Barca, strengthened their control over the territory, which by then stretched from Gibraltar to the Sistema Central mountain range, trying to increase their power over the region to prepare for an inevitable second confrontation with Rome. According to legend, Hamilcar made his son, just a boy at the time, profess eternal hatred towards Romans.

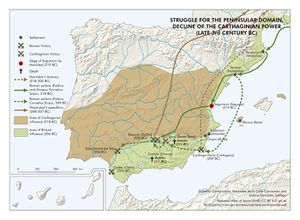

The geographical extent of Carthaginian power was restricted by a border treaty with Rome established in 226 BC, which set the Ebro River as the upper limit of their expansion to the north. It was the seventh such agreement. In 219-218 BC, Hannibal laid siege to the city of Saguntum, an ally of Rome despite its location to the south of the Ebro River. Rather than accept imminent defeat, the Saguntians preferred to commit suicide and burn the city to the ground. The news outraged the Roman Senate; the conquest of Sagunto was considered a casus belli.

Hannibal advanced further, commanding his forces across the Ebro River towards Italy on a famed expedition through the Pyrenees and Alps with his forty legendary war elephants. The reaction of the Romans after losing four memorable battles was to undertake an organised military strategy. Meanwhile, Hannibal had reached Capua but had decided against storming the city of Rome. At one point, the supplies he had sent to his brother, Hasdrubal, in Emporium (Empúries, Girona) were ultimately cut off by Roman forces led by Gnaeus and Publius Cornelius Scipio, who had disembarked there in 218 BC. After engaging in several successive battles (Carthago Nova in 209 BC, Baecula in 208 BC, Ilipa in 206 BC, and Gades (Cádiz) in 205 BC) these Roman expeditionary forces eventually succeeded in destroying and replacing the Carthaginian Empire on the Iberian Peninsula.

The Ancient Age was a period characterised by conquest and Romanisation of the Iberian Peninsula. This Roman control over the Peninsula led to the widespread use of the Roman term Hispania when referring to the collective peninsular territories. Gradually, the inhabitants of Hispania adopted the politics, language, culture, way of thinking and lifestyles of the Roman empire.

|

The formation of Roman Hispania Romanisation on the Iberian Peninsula was a slow, gradual process by which Rome progressively brought the territories of Hispania under its rule. This movement had taken hold starting in the year 218 BC and endured until the end of the 1st century BC, when the diverse peninsular communities had been fully integrated into a single unified territory with a common economy, language and culture. |

The construction of Roman roads uniting the now very Romanised 150 cities in Hispania facilitated a rapid distribution of raw materials and merchandise. The development of highly-advanced technology enabled them to go through mountains and rivers as well as the construction of queducts, civic centres, sports complexes, institutional buildings and recreational spaces. The road system ran north-south with two major thoroughfares: Vía de la Plata, from sea to sea, and Vía Augusta, extending all the way to the city of Rome. These two roads were linked in turn from east to west by two parallel roads originating in Asturica Augusta and Italica. And lastly, there was a diagonal causeway joining Emerita Augusta with Cesaraugusta.

Navigating the coastline along the extension of the Mare Nostrum and up to Rome was faster and cheaper than travelling by land. Transport ships enabled the crossing of rivers such as the Guadalquivir to reach Corduba, the Guadiana to reach Emerita Augusta, and the Ebro to arrive in the cities of Cesaraugusta (where the port is visible) and Calagurris.

Production on the Peninsula at this time was primarily based on agriculture, livestock and mining. Cultivation of the Mediterranean dietary trilogy of wheat, olives and wine as well as the herds of horses and flocks of sheep were the basis of wealth in Hispania. While the successful exportation of wine, oil, wool and garum (a unique seasoned sauce produced in the southwest) brought prosperity to prominent Hispano-Roman families, the mining of metals was an even more lucrative enterprise. There were numerous mining settlements and drilling was commonplace. Sophisticated extraction techniques such as the ruina montium were used. This technique involved the digging of cavities in mountains, which when filled with water, fragmented the rock walls. Though inadvertent, this technique produced spectacular landscapes like Las Médulas. Mining also greatly increased the wealth of the Roman State, both from its own mining operations or by collecting money from private mining companies financed by aristocratic capital.

The strong economic growth of Hispania and its integration into the Roman Empire afforded the wealthy Hispano-Roman clans the privilege of obtaining Roman citizenship. Three centuries later, in 212, the Edict of Caracalla granted citizenship to all inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula.

In the rural areas, a rich, ancestral palace of a noble man was called a villa; the same name was indistinctively given to a nobleman's agricultural exploitation of his land and his peasants' small villages, which included their bakeries, blacksmith's, carpenter's, mills and ponds. The aristocratic land owners retreated to these villas during the crises of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, periods which brought economic insecurity and in effect, misery. Rural life guaranteed a level of subsistence that the cities could no longer provide.

Facing the crisis of the 3rd century, Diocletian (284-305) carried out an administrative, military and economic restructuring of the Roman Empire. The three provinces of Hispania were divided into five regions: Tarraconensis, Cartaginensis, Baetica, Lusitania and Gallaecia. However, economic reform brought poverty. Slaves, who were very costly, were emancipated and inevitably became peasants, servants, manual labourers, and even, personal bodyguards for the lords and their possessions. The development of this system of multiple autonomous regions with a central governing power (which also protected life against hunger or thieves), forebode the manorial system of feudalism.

Co-authorship of the text in Spanish: María Sánchez Agustí, José Antonio Álvarez Castrillón, Mercedes de la Calle Carracedo, Daniel Galván Desvaux, Joaquín García Andrés, Isidoro González Gallego, Montserrat León Guerrero, Esther López Torres, Carlos Lozano Ruiz, Ignacio Martín Jiménez, Rosendo Martínez Rodríguez, Rafael de Miguel González. See the list of members engaged

The transition to the Middle Ages

Rural Hispania aided the successive arrival of Barbarian tribes to the Iberian Peninsula throughout the 5th century. They came by virtue of agreements or foedus (the root of the word feudal) negotiated with the remote imperial power of Rome, in turn, felt obligated to show them some level of hospitalitas. They had not come to wage war, so upon their arrival, only some cities, run by their bishops, closed its doors to them. Moreover, they were rarely met with hostility, except on the occasions when some group joined together with gangs of Bagaudae (organised thieves). In any case, this Barbarian presence on the Iberian Peninsula went virtually unnoticed in a population of perhaps four million people.

The Suevi arrived around 409, the Vandals, around 411 and the Alans about 418. After intermingling with the Hispano-Romans, the Suevi were the only group of people during the 5th and 6th centuries able to establish their own state. The first Visigoths arrived on the Iberian Peninsula between the years 414 and 417. As allies of the Roman Empire and in exchange for this loyalty, they were awarded a giant swath of land spanning from the Loire to the Ebro rivers. In this region, they went on to establish their capital city, Toulouse. The Visigoths contributed to the victory of the Orleans Battle against the Huns in 451 and founded the first court of law in Barcelona. They expelled the Alans and Hasdingi Vandals from the Iberian Peninsula. A second wave of immigrants arrived in Hispania between 466 and 484. When the Franks defeated the Visigoths in the Battle of Vouille in 507, they settled south of the Pyrenees and Toledo became their new royal seat, circa 540.

Over the course of the 6th century, Hispania gradually ceased to be Hispano-Roman and by the 7th century, started to become Hispano-Germanic. With King Leovigild at the helm (568-586) the Visigoths united the territory and attacked the villages in the north (573-581) as well as the Suevi (585) and the Byzantines, who had arrived on the Peninsula during the territorial expansion led by Emperor Justinian. Recared (586-601), Leovigild's successor, renounced Arianism, the official Visigoth religion and accepted the Nicene Creed, as did the Hispano-Romans. King Suintila (621-631) expelled the last of the Byzantines and it is posited that King Recceswinth may have been the leader who in 654 unified the Germanic and Latin laws to create the Visogothic law code Liber iudiciorum. This legal system was in effect in the Hispanic kingdoms throughout the High Middle Ages. The institutional structure of the Visigothic Kingdom included legislative assemblies (the concilios) where nobles and clergymen took decisions, great halls in an imperial or royal palace (aula regia or cincilium regis), a Royal household imitating the Roman Imperial Model (officium palatinum), borders, an army, and a currency. Saint Isidore recognised in his Laus Hispaniae that: "You are, oh Hispania, sacred mother... the most beautiful of all lands... from the West to India... You are the honour and ornament of the world, the most illustrious... And therefore... golden Rome loves you and... the nation of the Goths... it now rejoices in you... with security and happiness".

Co-authorship of the text in Spanish: María Sánchez Agustí, José Antonio Álvarez Castrillón, Mercedes de la Calle Carracedo, Daniel Galván Desvaux, Joaquín García Andrés, Isidoro González Gallego, Montserrat León Guerrero, Esther López Torres, Carlos Lozano Ruiz, Ignacio Martín Jiménez, Rosendo Martínez Rodríguez, Rafael de Miguel González. See the list of members engaged

You can download the complete publication Spain on maps. A geographic synopsis in Libros Digitales del ANE site.